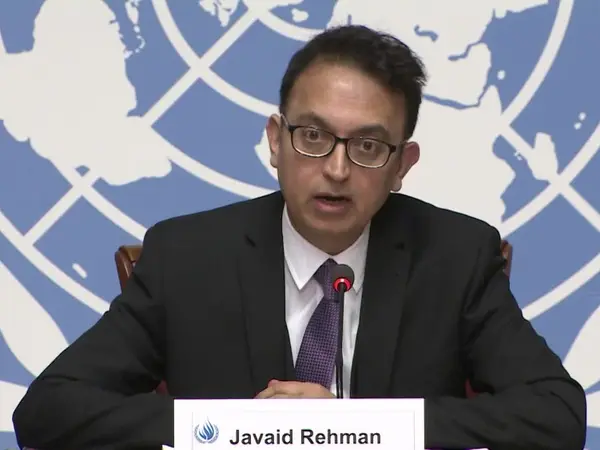

Javaid Rahman, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights in Iran, has said a UN vote had increased the likelihood of “violence and repression.”

Rahman was speaking after the UN Human Rights Council voted November 24, by 25 votes to six with five abstentions, to establish a fact-finding investigation into deadly government violence against protesters.

In an interview with Reuters news agency, the special rapporteur, said he was concerned at a “campaign” of death sentences over recent protests in Iran, which has a high incidence of capital punishment: “I’m afraid that the Iranian regime will react violently to the Human Rights Council resolution and this may trigger more violence and repression on their part.”

According to Norway-based HRANA, November 286, 451 protestors and 60 members of the security forces have been killed in protests since September 17, the day after the killing in custody of Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini. Just over 18,000 people have been arrested. Rahman told Reuters that six of those arrested had this month been sentenced to death.

"Now (authorities) have started a campaign of sentencing (protesters) to death," he added, saying he expected more to be sentenced.

Already, 21 people arrested in the context of the protests face the death penalty, including a woman indicted on "vague and broadly formulated criminal offences", and six have been sentenced this month, Rehman said.

Budget, staff, evidence

The mission set up by the UN vote will have a $3.67 million budget and 15 staff, the news agency reported, but Rahman, who has not been allowed to visit Iran since he was appointed in 2018, did not explain what course of action he intended beyond an aim to “collect, consolidate and analyse evidence.”

Iran this week announced that it will not cooperate with the UN investigation, which means Rehman will continue to be persona non grata.

Rehman said he expected the mission to gather a list of perpetrators to be shared to national and regional legal authorities to “ensure accountability and…provide evidence to the courts and tribunals.”

The special rapporteur therefore appeared to evoke universal justice, under which states or international bodies pursue serious cases – usually crimes against humanity – regardless of where the alleged crime took place.

Universal jurisdiction

In July a court in Sweden sentenced to life imprisonment Hamid Nouri, a former Iranian official, over 1988 prison massacres in Iran, three years after he was arrested after arriving in Stockholm on holiday. In January a German court jailed for life Anwar Raslan, a former Syrian intelligence office earlier granted asylum, for murder and rape of prisoners in Damascus.

But such successes are rare. Notable failures in universal jurisdiction include Britain’s 1998 arrest under a Spanish warrant of former Chilean dictator Augustine Pinochet and the 2001-3 prosecution in Belgium of former Israeli premier Ariel Sharon over the 1982 massacres in Beirut’s Sabra-Shatila Palestinian camp. The US has generally eschewed universal jurisdiction, refusing to join the International Criminal Court. President Donald Trump in 2019 pardoned three US soldiers implicated in war crimes in Iraq, and President Joe Biden recently granted immunity to Mohammad bin Salman although US intelligence regards the Saudi crown prince as responsible for the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul.